Lessons from Influenza: How COVID-19 Could Evolve Toward Endemic Status Amid Disease Control Challenges and Misinformation

By Asia McGill

Health experts believe coronavirus is likely here for good, and its endemic stage will develop a seasonal pattern like its predecessor the flu. However, unlike the Spanish flu pandemic that ended within two years, the Covid-19 pandemic is approaching three years.

In 1920, after spreading for two years, the flu reached its endemic stage mostly because the people who carried the virus died or became immune. Eventually, vaccines helped curb the flu as well. Similar to COVID-19, there were hurdles controlling the spread of the disease. Initially, World War I contributed to the spread of the flu as troops were regularly transferred overseas.

Though the flu pandemic had a shorter duration than coronavirus has so far, both shared the same characteristics: resistance and inconsistent reporting.

The Columbia School of Public Health reports that a pandemic becomes endemic when the disease is still consistently present, but limited to a particular region.

Throughout history, pandemics typically have a life-span of two to three years.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of Nov. 9 the total number of weekly cases in the United States stands at 288,989, a drop of nearly 180% from the highest count of cases recorded this year on Jan. 19, 2022.

COVID is in a longer recovery stage compared to the flu. Despite the significant decrease in cases, experts have not declared the disease is now endemic.

Dr. Jean Boyer, an immunologist at Celsion Corporation who studied the behavior of diseases believes controlling COVID may be “a timing thing.”

Boyer notes that COVID-19 has killed six million people worldwide and a million in the United States. It is “more deadly in vulnerable populations,” she said.

The vulnerable populations include impoverished communities that had limited access to good healthcare and vaccine opportunities at the peak of the pandemic, as well as frail, elderly residents or those who are immune compromised.

Developing vaccines proved difficulty because COVID-19 mutates so quickly. Once the first vaccine was approved, access had been limited, especially in impoverished communities, leading to an even higher demand, according to the experts.

“There are mutations followed by outbreaks within weeks to months. We can't make a vaccine that quickly,” Boyer said.

Vaccination hesitancy

When the vaccine first emerged, some Americans questioned the safety as it had been fast tracked. Because of this, many Americans were hesitant to get vaccinated, which contributed to the fast spread of the disease, experts said.

A December 2021 survey conducted by the United States Census Bureau found that 15% of Americans were against the vaccine and chose to remain unvaccinated.

During last year’s winter holidays more than a million unvaccinated Americans died from coronavirus, according to the CDC.

Initially, many Americans were hesitant to get COVID vaccines even though the flu vaccine has become routine, experts said.

However, it is important to note the difference in how each vaccine was developed.

“Flu sequences are tracked six months before an outbreak,” Boyer said.

This gives immunizers a jump toward developing the most up to date vaccine to combat the mutations for the next flu and cold season.

It is more complex for COVID-19 vaccines as researchers around the world are still learning how the virus behaves, which is not as predictable as the flu.

While healthcare officials said underreporting still remains an issue for COVID-19, it is not to the extent that it was during the flu pandemic because of the war. Around the world, militaries did not disclose that soldiers were too sick to fight. The weakened troops may have contributed to ending the war, say some historians.

Data analyzed by the World Health Organization (WHO) showed that the spread of coronavirus was not only due to massive underreporting, but many believed the virus itself was not real, and virtually harmless.

Former president Donald Trump ignited controversy across the nation as he dismissed the seriousness of COVID-19, suggesting the virus was no worse than the flu.

"This is a flu. This is like a flu," Trump said during a coronavirus task force briefing in 2020 that he often repeated during national televised briefings.

Within a year after COVID-19 emerged in the United States, the first round of vaccines were administered, which were originally only authorized for the elderly and immunocompromised.

Tithi Patel, a staff pharmacist at CVS Pharmacy in Lawrenceville, was one of the many frontline workers when the vaccine was released.

Vaccine distribution to the pharmacy was extremely limited, which led to vaccinations by ‘appointment only.’

“A lot more pharmacies had the vaccine readily available,” Patel said.

Patel also experienced great difficulty administering the vaccine to patients who already had a fear of the vaccine and needles. Patel said some of the fears she has heard from her patients included the scars they still had from childhood vaccines.

While Patel noted that most New Jersey residents are vaccinated, many patients are still coming in for their first dose whether by personal decision or as a job requirement.

“Patients are forced by their jobs or employers to get the vaccine,” Patel said.

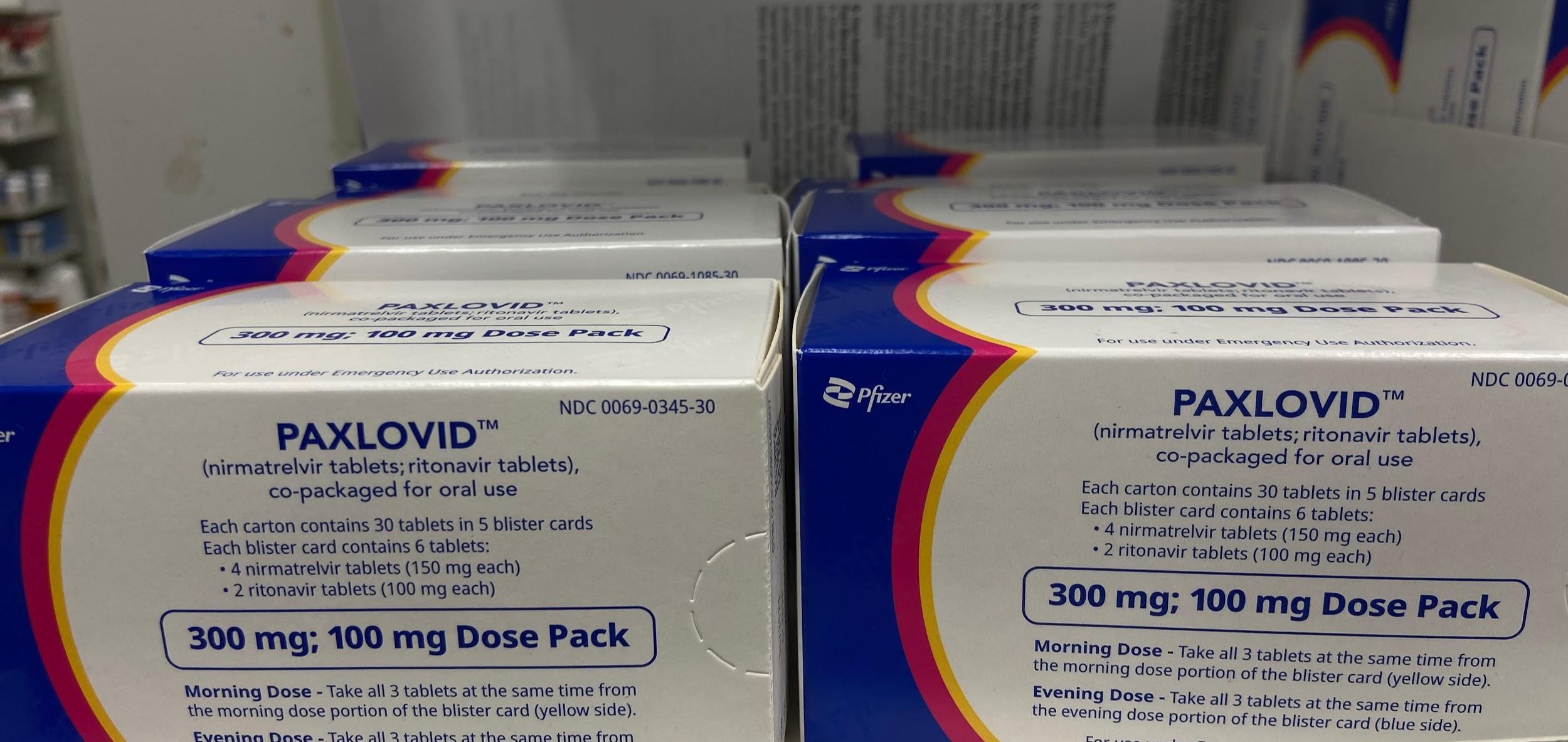

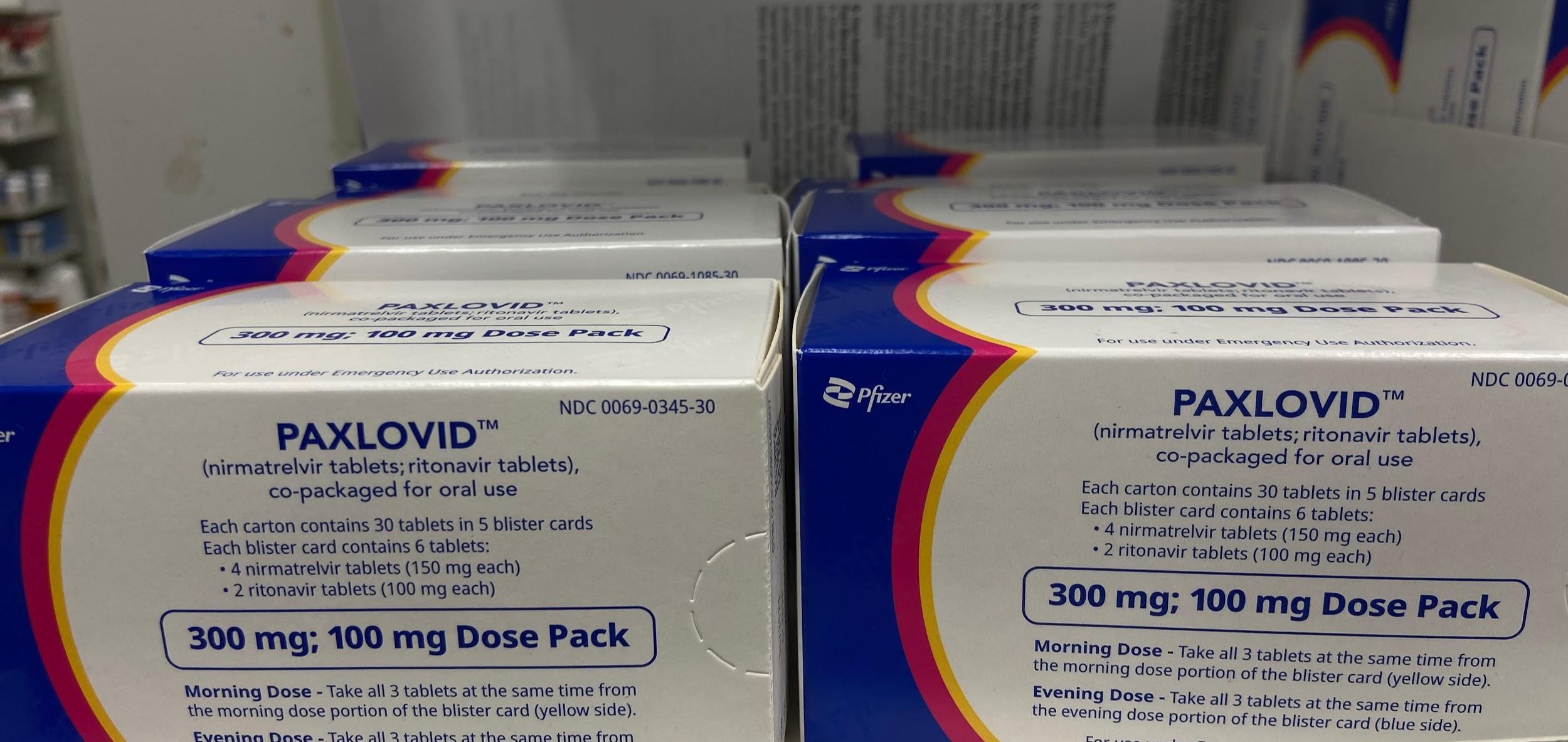

According to the CDC the Pfizer vaccine has an efficacy rate of up to 90% as of August 2022. Patel said there are also treatments to reduce the severity of COVID-19, such as Paxlovid.

Paxlovid is an antiviral that has been used to treat and relieve COVID-19 symptoms in its early stages and has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since December 2021.

A clinical study conducted by the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR) showed that Paxlovid reduced the risks of hospitalizations and death by 88%.

Patel receives a few patients a day with Paxlovid prescriptions, and noted its effectiveness in the downward trend of cases, adding, “We have settled down as we’ve returned to normalcy.”

Patel has confidence that Americans are reaching the tail end of the pandemic, and predicts it’s going to “follow a very similar pattern as the flu.”

Similar to the initial COVID-19 practices, in the 1920s flu patients were mandated to quarantine and maintain good personal hygiene. However, sick flu patients did not have antiviral treatments to ease the symptoms.

At the time, health professionals used herbal remedies according to Herbal History. Herbal History reported the use of some herbal remedies have a 75% efficacy rate in treating flu symptoms, making the virus more manageable.

In the late 1990s, the FDA approved Tamiflu, an antiviral treatment used to treat flu symptoms and speed the recovery time. With Tamiflu, health officials found patients recovered more quickly from the flu.

When taken within two days of exposure, the National Center for Health Research found that Tamiflu can reduce complications by 44% and hospitalizations by 63%.

Steps toward normalcy

The White House last month proposed the National COVID-19 Preparedness Plan, an outline of what the next steps for the country are as the anticipated endemic stage approaches for COVID-19.

“We look to a future when Americans no longer fear lockdowns, shutdowns, and our kids not going to school,” according to the plan.

The plan details strategies to increase vaccinations and routine testing. and provide counseling for those who have experienced loss.

To date, the coronavirus and the Spanish flu have been the deadliest viruses in the world, each killing millions.

While treating the flu pandemic, researchers learned the importance of quarantines and yearly vaccinations. With COVID-19, researchers around the world collaborated to quickly develop vaccines and treatments.

The day the CDC announces the end of an almost three-year pandemic is not something health officials are now predicting. With the drop in cases and success vaccinating and medicating the American population, the end is not as improbable as it appeared this time last year, the experts said.

Health officials in the United States have been watching holidays closely. Families congregate inside, often with members that may come from other parts of the country or world that could lead to spikes.

In How to Approach the Holidays New York Times writer Jonathan Wolfe recommends that the best way to approach the holiday punch is for gatherers to get tested beforehand, have a short term quarantine, and if you go out with friends, try to meet them outside.

The CDC’s case number trends revealed that the Thanksgiving spike is nowhere near the severity it was last year, with a 75% decrease in positive cases. The country’s next hurdle will be the upcoming winter holidays.

Post a comment